Biodiversity and Information

This theme develops an

understanding of Biodiversity and the way it contributes to Ecological

Function via embodied information. Here we mean far more than

counting species to quantify biodiversity: the diversity of life is to

be found among genes, proteins, cell-types, behaviours, body-plans,

and ecological community structures. Because diversity is a measure of

difference, specifically the number of different ways a system's

components can differ, it is very closely related to information

content and many methods of statistical information theory apply to

help understand these connections. Because we can describe biodiversity

in terms of embodied information in living communities, we find a unity

between ecological and organism-level accounts of living processes.

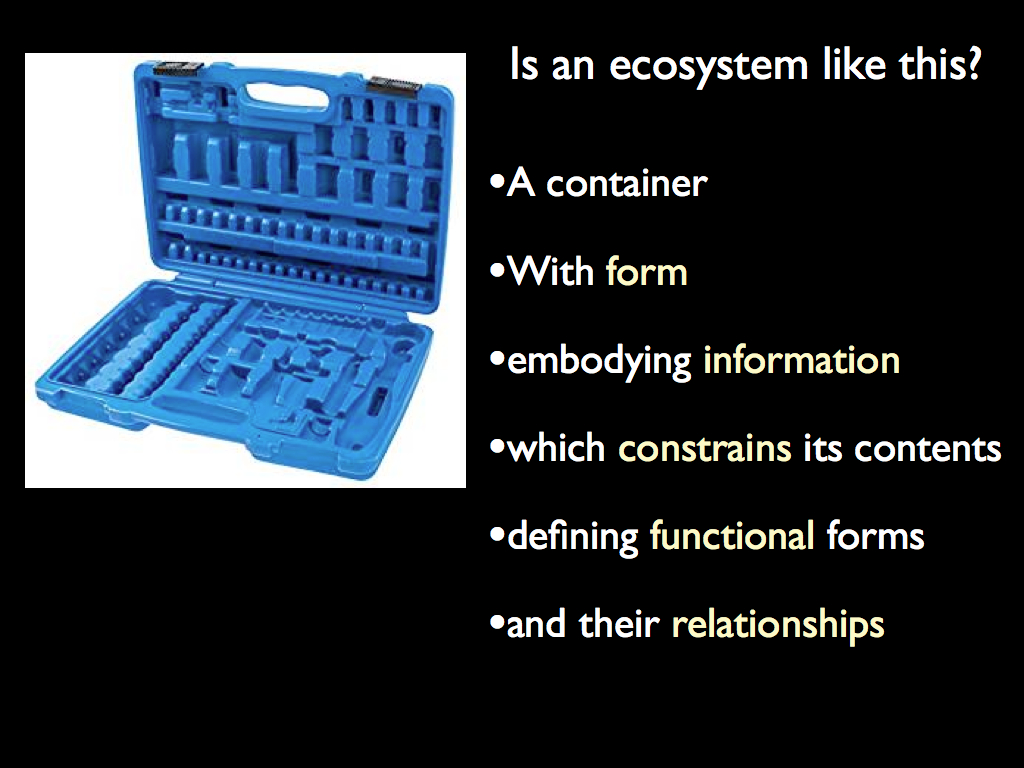

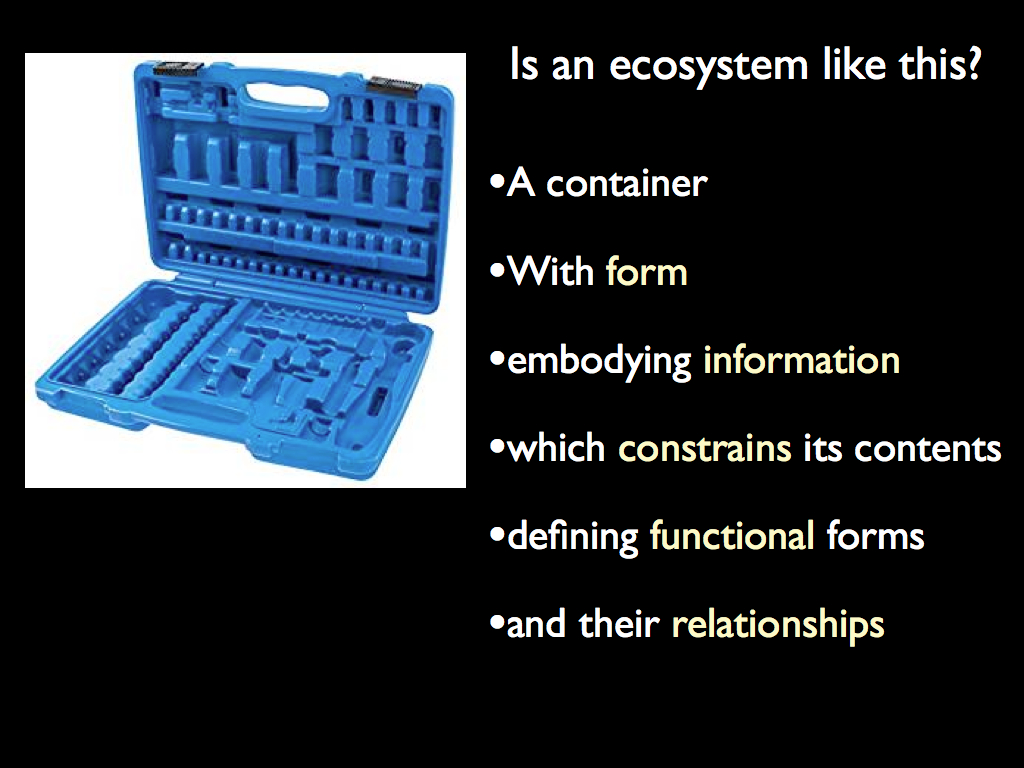

This unity is supported by the common origin of all life and all but one of the

features of autopoiesis

found at the organism level. What is missing from that at the

ecological level of organisation is only the containing boundary:

ecological communities conspicuously have no identifiable boundary,

over which we can say this species is inside and that one is outside.

We will

find that some (unknown) fraction of the information instantiated by an

ecological community (which we can quantify with biodiversity) is

functional

in the sense we use on

these pages. It is conjectured that the total of all the ecological

interactions among the organisms of a community constitutes a coherent

whole - a cybernetic system that acts as a transcendent complex: this is the topic of our "Ma of Ecology" page, illustrated below.

You will find a copy of Keith Farnsworth's introductory lecture slides on biodiversity here and a more advanced presentation (given to Imperial College, London in 2018) here.

You will find a copy of Keith Farnsworth's introductory lecture slides on biodiversity here and a more advanced presentation (given to Imperial College, London in 2018) here.

For those interested in

biodiversity metrics:

There is a page explaining the 'state of the art' on biodiversity indices and metrics here.

There is a page explaining the 'state of the art' on biodiversity indices and metrics here.

This Theme aims to:

- Develop a comprehensive, but strict and quantitative definition

of biodiversity

- Understand functional diversity at the ecological level

- Build from these an understanding of how ecological functions arise from functional information.

But first, let us consider:

What (really) is

Biodiversity?

Behind the myriad ways of measuring and describing biodiversity (see more detail here) there is a simple unifying quantity. The word 'biodiversity' literally means the diversity within a biological system, where diversity quantifies the total difference among the system's parts. So biodiversity is a measure of the total difference among the components of a biological system. Total difference is the number of ways in which the component parts of the system can differ from one another. (You can read more about this here.) This is equivalent to the total information instantiated by the system, both as an ensemble of components and including the information content of its organisational structure. That is not information about the system, but the natural information contained within it. This diversity is understood to arise at genetic, species and multiple levels of community organisation, hence is multidimensional in nature. Biodiversity indices have proliferated in attempts to capture this complexity but may now have confounded our efforts with their variety.

Broadly speaking, biodiversity arises from phylogenetic variation (e.g. species differences), ecological structure (the network of interactions and population abundances) and the diversity of functions performed by system components (e.g. nitrogen fixing). Together, these form three major axes of biodiversity (see Lyashevska & Farnsworth 2012): implying that biodiversity is effectively three-dimensional. Of course that is a kind of simplification used to make the problem of quantification more tractable, but the concept behind it also helps to understand biodiversity as a source of ecological function. Clearly it is the functional diversity that directly relates to function, but this kind of diversity would be impossible without the components (phylogenetic variation) and structure (structural diversity) underlying it. The reason functional diversity is empirically (more or less) independent of these is that there are very many ways of combining phylogenetic and structural elements to produce a set of functions: again we see combinations at work and consequently find information content lying behind the diversity of function. Note, reading the 'Ma of Ecology' you will see that we strongly disagree with the standard notion of 'structure' used in ecology.

Ecologists often have practical reasons for estimating particular aspect of the biodiversity of a system and many have made it their career to do so. Most of the presently available concepts of biodiversity are not actually about the diversity of natural systems, but rather they describe the diversity of field samples (described further here). The most commonly described aspect of the diversity in an ecological community is the so-called 'structural', where a large range of indices are available for statistically summarising the count of taxa (usually species) and the distribution of organisms among these taxa.

All these measures are incomplete, partly because they miss phylogenetic and functional aspects of diversity and partly because they concentrate on only one of the several levels of organisation in biological systems (usually it is the species level). A few have set out specifically to characterise, for example genetic diversity, and this is an important advance, but we need to go much further in order to characterise total biodiversity.

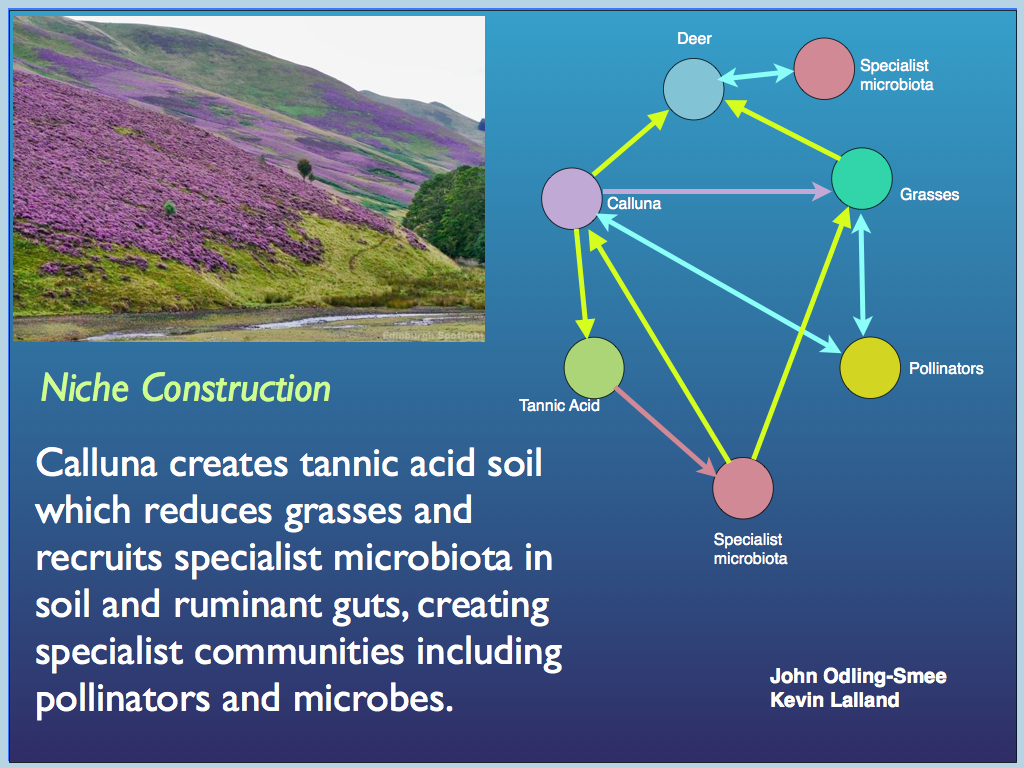

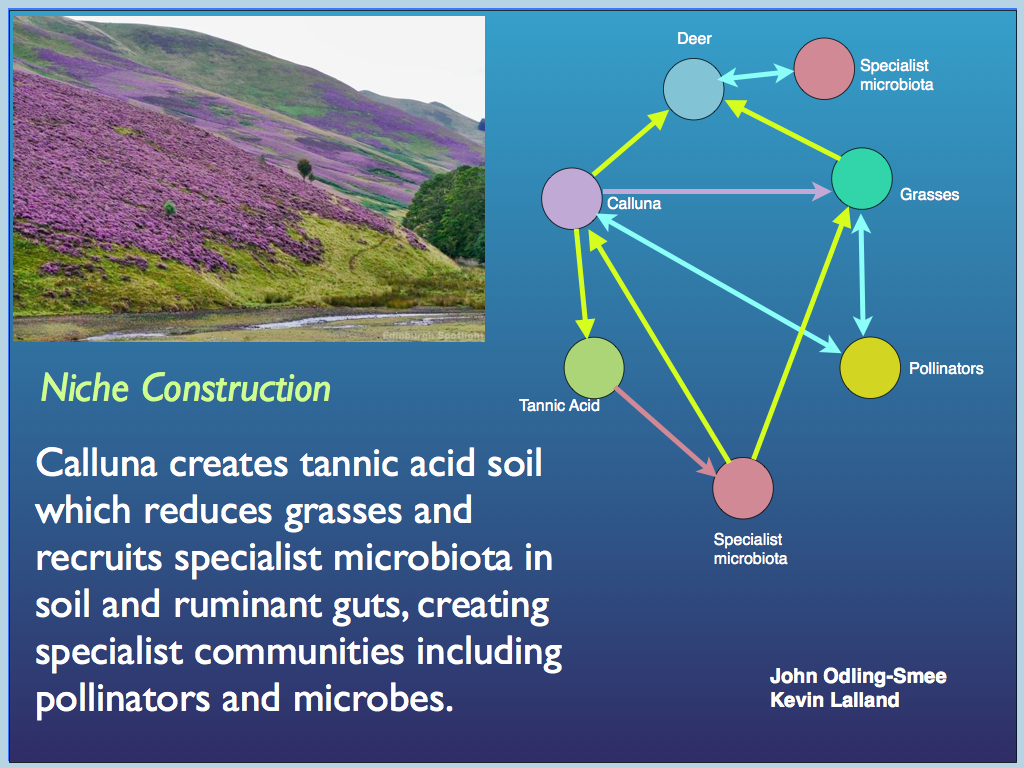

The reason we want to do that is two-fold. Firstly, because biodiversity, if defined this way, accounts for the information content of a biological system, which is of course the ‘commodity’ that concerns the idea of life as information processing. Secondly, if our definition of information is correct, it is this information, embodied in the system (which we might estimate by biodiversity), that gives a biological system its function. In particular, if the functional information can be identified, then we hypothesise that this is responsible for all the biological function. Not only that, but the ecological relationships (predator-prey, symbiosis, parasitism, competition) among the organisms form a network, which as embodied information could be interpreted as a cybernetic system capabable of downward causation, specifically selecting organisms for their functional contribution and 'computing' the system's set-point for resilience and robustness. This idea is a generalisation of the developing concept of Niche Construction Theory.

Crucially, not all the information embodied by an ecological community is biologically functional, so we also need a way to distinguish between functional information and all the rest. A working hypothesis is that this remaining information is random variation; i.e. it embodies no pattern (just as the random error in measurements spreads data about an empirical relationship in statistics). As a result of this notion, our focus is direceted toward finding ways of separating the functional from the random among the information embodied by biological systems.

One of the most important reasons for considering biodiversity more deeply is to understand the biodiversity-function relationship. It is not yet clear whether there is really anything to understand, in the sense of a regular pattern, or better still, an underlying mechanism for such a relationship among ecological communities. Many experiments suggest there might be, but we cannot get to the bottom of this until we understand precisely what biodiversity its different parts contribute to function at different levels of organisation. There are PhD opportunities for people who want to spend 3-4 years studying this sort of thing.

Behind the myriad ways of measuring and describing biodiversity (see more detail here) there is a simple unifying quantity. The word 'biodiversity' literally means the diversity within a biological system, where diversity quantifies the total difference among the system's parts. So biodiversity is a measure of the total difference among the components of a biological system. Total difference is the number of ways in which the component parts of the system can differ from one another. (You can read more about this here.) This is equivalent to the total information instantiated by the system, both as an ensemble of components and including the information content of its organisational structure. That is not information about the system, but the natural information contained within it. This diversity is understood to arise at genetic, species and multiple levels of community organisation, hence is multidimensional in nature. Biodiversity indices have proliferated in attempts to capture this complexity but may now have confounded our efforts with their variety.

Broadly speaking, biodiversity arises from phylogenetic variation (e.g. species differences), ecological structure (the network of interactions and population abundances) and the diversity of functions performed by system components (e.g. nitrogen fixing). Together, these form three major axes of biodiversity (see Lyashevska & Farnsworth 2012): implying that biodiversity is effectively three-dimensional. Of course that is a kind of simplification used to make the problem of quantification more tractable, but the concept behind it also helps to understand biodiversity as a source of ecological function. Clearly it is the functional diversity that directly relates to function, but this kind of diversity would be impossible without the components (phylogenetic variation) and structure (structural diversity) underlying it. The reason functional diversity is empirically (more or less) independent of these is that there are very many ways of combining phylogenetic and structural elements to produce a set of functions: again we see combinations at work and consequently find information content lying behind the diversity of function. Note, reading the 'Ma of Ecology' you will see that we strongly disagree with the standard notion of 'structure' used in ecology.

Ecologists often have practical reasons for estimating particular aspect of the biodiversity of a system and many have made it their career to do so. Most of the presently available concepts of biodiversity are not actually about the diversity of natural systems, but rather they describe the diversity of field samples (described further here). The most commonly described aspect of the diversity in an ecological community is the so-called 'structural', where a large range of indices are available for statistically summarising the count of taxa (usually species) and the distribution of organisms among these taxa.

All these measures are incomplete, partly because they miss phylogenetic and functional aspects of diversity and partly because they concentrate on only one of the several levels of organisation in biological systems (usually it is the species level). A few have set out specifically to characterise, for example genetic diversity, and this is an important advance, but we need to go much further in order to characterise total biodiversity.

The reason we want to do that is two-fold. Firstly, because biodiversity, if defined this way, accounts for the information content of a biological system, which is of course the ‘commodity’ that concerns the idea of life as information processing. Secondly, if our definition of information is correct, it is this information, embodied in the system (which we might estimate by biodiversity), that gives a biological system its function. In particular, if the functional information can be identified, then we hypothesise that this is responsible for all the biological function. Not only that, but the ecological relationships (predator-prey, symbiosis, parasitism, competition) among the organisms form a network, which as embodied information could be interpreted as a cybernetic system capabable of downward causation, specifically selecting organisms for their functional contribution and 'computing' the system's set-point for resilience and robustness. This idea is a generalisation of the developing concept of Niche Construction Theory.

Crucially, not all the information embodied by an ecological community is biologically functional, so we also need a way to distinguish between functional information and all the rest. A working hypothesis is that this remaining information is random variation; i.e. it embodies no pattern (just as the random error in measurements spreads data about an empirical relationship in statistics). As a result of this notion, our focus is direceted toward finding ways of separating the functional from the random among the information embodied by biological systems.

One of the most important reasons for considering biodiversity more deeply is to understand the biodiversity-function relationship. It is not yet clear whether there is really anything to understand, in the sense of a regular pattern, or better still, an underlying mechanism for such a relationship among ecological communities. Many experiments suggest there might be, but we cannot get to the bottom of this until we understand precisely what biodiversity its different parts contribute to function at different levels of organisation. There are PhD opportunities for people who want to spend 3-4 years studying this sort of thing.

The Theme is written by Keith Farnsworth