Dr Keith D. Farnsworth

Reader in

Theoretical Biology (retired)School of Biological Sciences,

Queen's University Belfast

United Kingdom.

Email: k.farnsworth (at) qub.ac.uk

BSc. (Hons) Astrophysics, University of London 1984

MSc. Acoustics, Southampton, 1985;

PhD. Mathematical Biology, Edinburgh 1994

MSc. Public Health Epidemiology, Aberdeen 2002

Here is a list of highlighted Publications The full set is available on Google Scholar

Also on ResearchGate, of course (and I'm on Academia, but have not visited them since they changed their terms and conditions). I also talked Queen's University Belfast into keeping my automated profile there: Pure (where they seem to have demoted me).

For a bit of nostalgia, please take a look at my Research Team page - those were the days!

About me:

I am a theoretical biologist, last employed by the Queen’s University Belfast (from which I retired in 2024). In defiance of the current fashion (led by anxious funding agencies) for applied research, I am trying to develop the deepest possible understanding of what life is and how it works (in a material universe). That is the main subject of this website and the elaboration of the slogan 'living is information processing' [1] is the central theme of my work and scientific contribution. Though this is unapologetically fundamental theoretical work, it has already spun out some applications: a better understanding of the value of biodiversity [11]; a way of explaining pain [4] that helps identify those organisms that may be able to suffer it; and ideas to improve the energy efficiency of the economy - just a few. By providing an understanding of the origin of physical causes, I have been able to offer explanations for several 'mysteries' of the physics of life: downward causation, autonomy, synergistic information and the emergence of complex systems such as ecological communities are good examples, so I think the theory is proving successful. With the rise of AI, its ability to distinguish life from non-life may become crucial.A lot of my previous work was more or less motivated by employers and funding agencies. My deeper theoretical enquiries were ‘curiosity driven’ and led me from information theory and cybernetics, to causation and what has been termed ‘the organisational approach to biological systems’. On the way, I have proposed a modernisation of Aristotle’s four aspects of cause, especially identifying formal cause with information embodied in the pattern of matter; and interpreting efficient cause as the empowerment of formal cause with physical force [2, 8]. So far that is proving very useful in constructing explanations for biological autonomy (previously thought a mystery), behavioural motivation and biological function [3, 4, 5, 6]. The organisational approach helps us understand why organisms are special in the sense of causation and agency [3, 7, 9] and is certainly open to philosophical approaches. The central idea is that of closure to efficient causation: unique to organisms and without which, agency cannot be attributed. It seems like a purely philosophical idea, but I have shown 'closure to efficient causation' and its linear relative 'downward causation' to be real physical phenomena. I am not alone in this, of course. A lot of the pioneering work (e.g. by Rosen, Varela and Maturana, Kauffman, Pattee and many others) has necessarily been quite abstract, but recently, people like Jannie Hofmeyr and Marcello Barbieri have built much more biochemical realism into our explanations. At the moment my contribution seems to be linking these and the physics and information theory that describes their cybernetic underpinning. It's an exciting ride - for those that like that sort of thing.

[1] Farnsworth, K.D., Nelson, J., Gershenson, C., 2013. Living is information processing: From molecules to global systems. Acta Biotheor. 61, 203–222. doi:10.1007/s10441- 013-9179-3.

[2] Farnsworth, K.D., 2022. How an information perspective helps overcome the challenge of biology to physics. BioSystems 217, 104683. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j. biosystems.2022.104683.

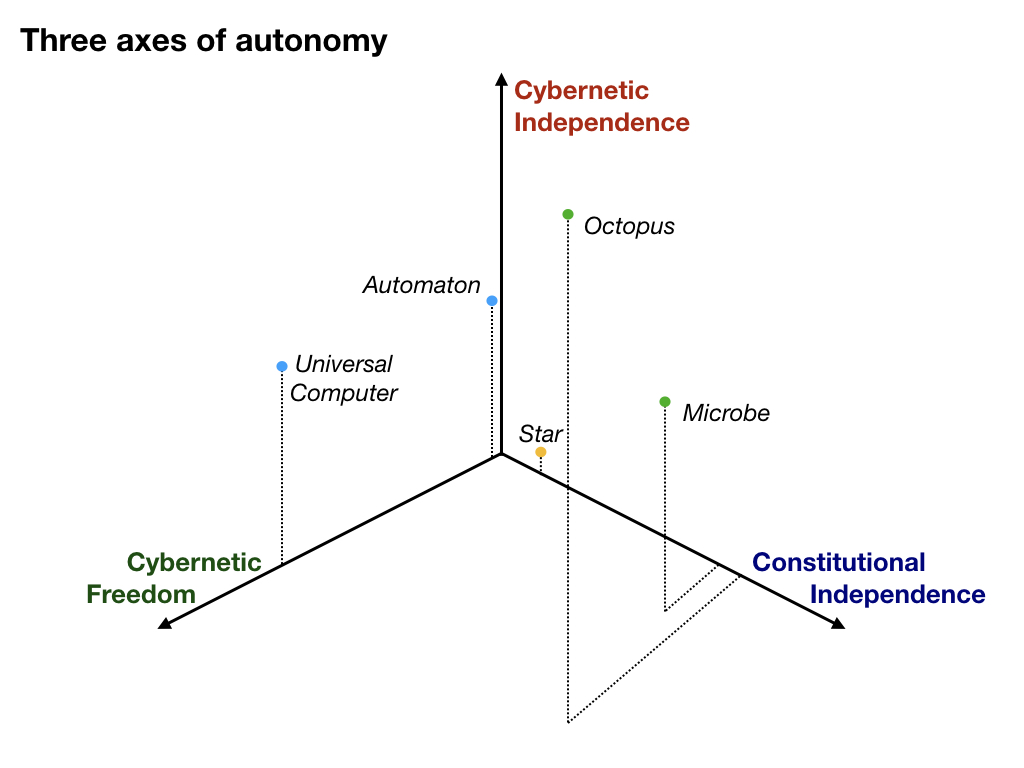

[3] Farnsworth, K.D., 2018. How organisms gained causal independence and how it might be quantified. Biology 7, 38. doi:10.3390/biology7030038.

[4] Farnsworth, K.D. and Elwood, R.W. 2023. Why it hurts: with freedom comes the biological need for pain. Animal Cognition, 1-17. doi:10.1007/s10071-023-01773-2.

[5] Farnsworth, K.D., Albantakis, L., Caruso, T., 2017. Unifying concepts of biological function from molecules to ecosystems. Oikos 126, 1367–1376. doi:10.1111/oik.04171.

[6] Farnsworth, K.D., 2021. An organisational systems-biology view of viruses explains why they are not alive. BioSystems 200, 104324. doi:0.1016/j.biosystems.2020.104324.

[7] Farnsworth, K.D., 2017. Can a robot have free will? Entropy 19, 237. doi:10.3390/ e19050237.

[8] Farnsworth, K.D., 2025. How Physical Information Underlies Causation and the Emergence of Systems at all Biological Levels. Acta Biotheoretica 73 (2), 6.

[9] Farnsworth, K.D., 2025. Homeostatic set-points are physical and foundational to organism. Biosystems 105634.

(You can get more detail on my publications here)

More on my research activity

What is Life?

Starting with biodiversity

My expedition into biological information and function started with thoughts about biodiversity. Rather than taking it for granted that this had to do with the number of species in a community, I sought to quantitatively define what biodiversity really is. I realised ‘diversity’ meant degree of difference and that is mathematically equivalent to the quantity of information. But this is not information about the community, it is information that is physically embodied in the structure and form of the organisms composing the community. So started an effort to quantify biodiversity in units of information: the sum of differences (i.e. complexity) in and among forms which physically embody the information [10,11]. Notably, biodiversity was a combination of genetic, functional and organisational diversity and the common factor among these was information- embodied at levels of organisation from molecular up to ecological. Indeed information turned out to be the essence of all living systems.

[10] Lyashevska, O., Farnsworth, K.D. (2012) How many dimensions of biodiversity do we need? Ecological Indicators, 18: 485-492.

[11] Farnsworth, K.D., Lyashevska, O., Fung, T.C. (2012). Functional Complexity: The source of value in biodiversity. Ecological Economics 11: 46–52.

Life as information processing

Life is not static information, it is constantly renewing, replicating and adapting: life itself, necessarily dynamic, therefore must be information processing. Paralleling John Von Neumann's insight into self-replication, it can be said that life is computation and what it is computing is itself. It was obvious that not all the differences, e.g. among leaf shapes or the markings on a shark, matter. A lot of this detail was just random. So what was needed was some quantifiable measure of functional information - loosely - that which causes a difference "that makes a difference" - to use Bateson's memorable phrase.

The idea of biological function, with all its awkward teleological implications had not been resolved at that point, so with colleagues, I set about to establish a generally applicable definition. The best starting point for one consistent with physical principles was the 'functional role' account attributed to Cummins (1970). Formalised and set in a more concretely physical context, that became a definition [5] using two important concepts: a) the hierarchy of organisation in living systems (from atoms, thought cells and organisms, to ecosystems) and b) causation as the physical expression of physically embodied information.

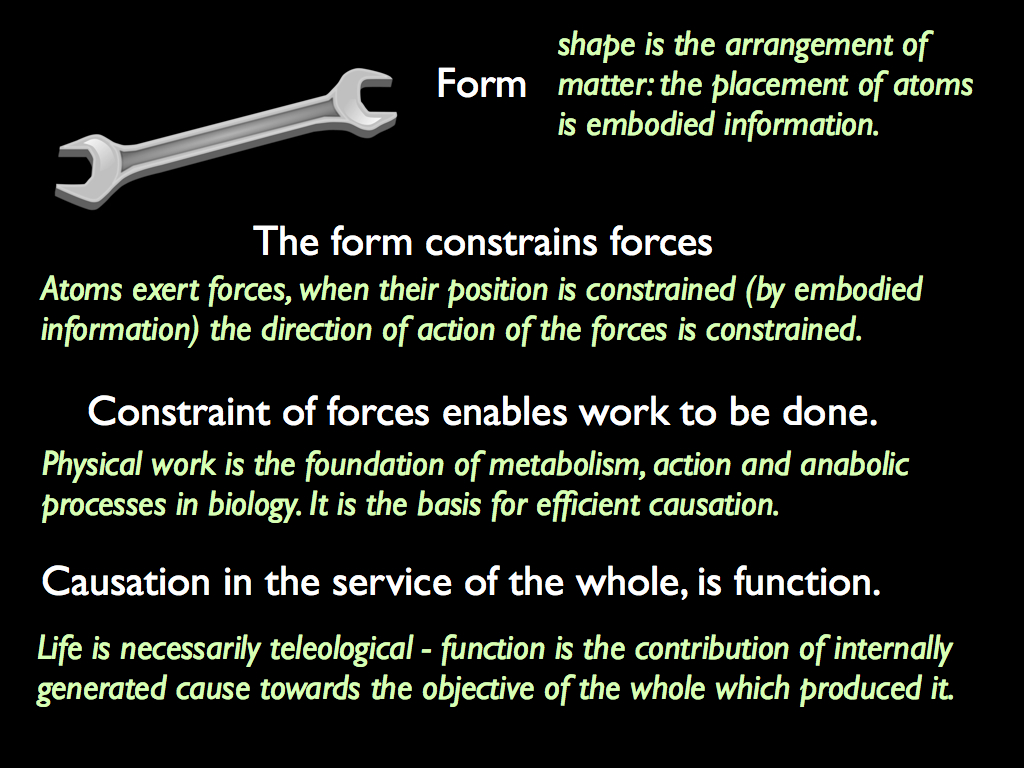

The next insight was to see that in the real world, causation always involved physical forces, hence underlying it is always one or more of the four fundamental physical forces fields that emanate from fundamental particles. Physical causation results from the constraint of the action of these forces, simply by virtue of determining the space-time locations of the particles (see figure below, from [2] and [6]).

This led me to define physical (i.e. embodied) information as a (stable) pattern in the locations of particles (to which we add formal information (a disembodied concept of physical information) and statistical information (the mathematical representation of physical information). The only one of these that is real is physical information, but cybernetics explains its behaviour and rules of interaction, while the mathematical treatment of statistical information (especially Shannon's communications theory) describes the phenomena that result from those behaviours and interactions.

In general, information constrains randomness by specifying the particular from among a random set of possibilities (diagram above: A random unconstrained; B simple strong constraint, as in a crystal; C more complicated constraint of interaction among molecules and D functional effect of dynamic morphological constraint in enzyme action, as in the 'lock and key mechanism'). We can imagine a pattern 'p' and replicate it to make a set P={p1 p2 p3 ... pn}, then arrange the copies in space-time, with coordinates Z={z1, z2, z3, ... zn}, i.e. a pattern of patterns. This higher level pattern then contributes to dictating the coordinates of each elementary particle from which the p are made. It is that contribution - higher level information - that constitutes downward causation. In life, the set P is arranged through physical forces arising from each element of each p - the interactions among the molecules of life. From this, we understand that molecules self-organise into patterns (networks and structures) that in turn affect the fate of those same molecules - this is the physical basis of closure to efficient causation (or to put it another way, the appearance of circular causation A->B->C->A that characterises life in general and reproduction in particular.

That idea enables a formal and general definition of biological function - constraint by information at one level that contributes to the constraint by information at the higher level to which it belongs is function.

Physically, life computing itself means that it constantly constrains the set of possible chemical reactions that take part within a cell, to only that small subset which collectively and continuously re-make the organism. The computation is in and among the biochemical reactions (elements of analogue computing), most of which, just as in a digital computer, are controllable. The action of an enzyme can be switched on and off by reversible changes in its shape in response to a control signal and networks of such signals amount to a computer (see [9]). Obviously, all talk of control implies constraint and thereby (according to my theory) physical information. The value of information is the constraint it provides, selecting what is functional from all that is not. An example of controllable biochemistry embodying a piece of information, separately from the rest of the world, so it belongs to the organism, is the set-point of a homeostatic control system (see [9]). Living cells are full of these control loops and they constitute the foundation of biological autonomy [3,7].

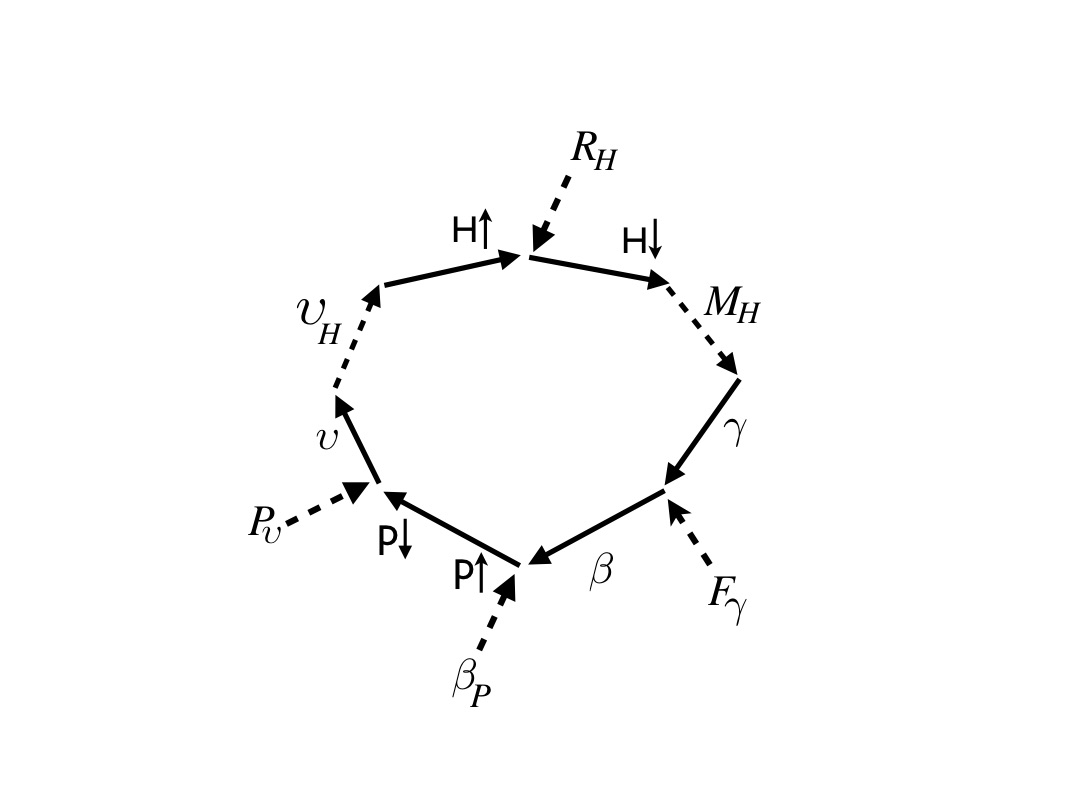

Understanding all this control and autonomy requires causal analysis and that has been developed and honed with biological examples, based on foundational work by Robert Rosen and followers, notably Jannie Hofmeyr. I illustrated my view of causation with the example of ATP-synthase: a marvelous little molecular machine found in all living cells: it recharges ATP from ADP and appears as a little dynamo (causal analysis diagram below, from [6]). This and similar analysis is confirming that physical causation is the constraint in the action of fundamental forces by information embodied as the relative coordinates of the particles from which the forces emanate [2,8]. This in turn gives a physical explanation to seemingly weird phenomena such as downward causation (it turns out is no more than higher level patterns of particle assembly contributing to constraining information) and the apparent circularity of closure to efficient causation, where everything is the cause of everything else, which is just the mutual interaction among patterns and patterns of patterns that unfolds in time (not simultaneously as multiple causes for a single event).

Causal analysis of ATP-synthase molecular machine (from [6] -- dashed arrows for efficient causes and solid for material cause, with labelled components: gamma and beta subunits, H protons etc. (see publication [6] for details).

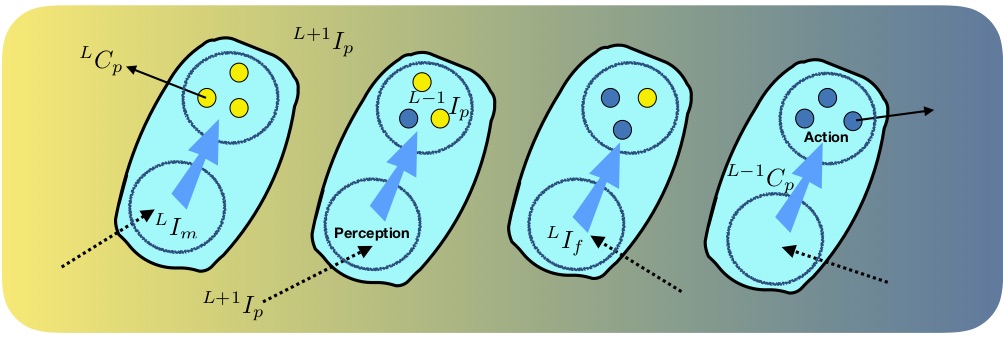

I had to develop a notation for dealing with multi-level causation when interpreted as the constraint of action of forces by embodied information (relative coordinates of component particles). In the illustration below (from [8], inspired by Mike Levin's work in developmental biology), the formation of a tissue (organisational level L+1) from individual cells (L) is mediated by molecular level (L-1) physical causes that scale up by diffusion to form a gradient in hormone concentration, embodying information at L+1, which is 'perceived' by cells, becoming internalised information that constrains the internal molecular (L-1) process, thus illustrating both upward (emergence) and downward causation.

Multi-level information and causation in tissue growth with cellular differentiation (from [8]).

Using the same methods, I was, reluctantly, able to show that an ecological community is probably not a thing in itself, i.e. it can be entirely accounted for by the organisms composing it - there is no underlying organisation into which they all fit. The fact that I did not find what I was hoping to, is testament to the explanatory power of the multi-level causal analysis - some consolation for me.

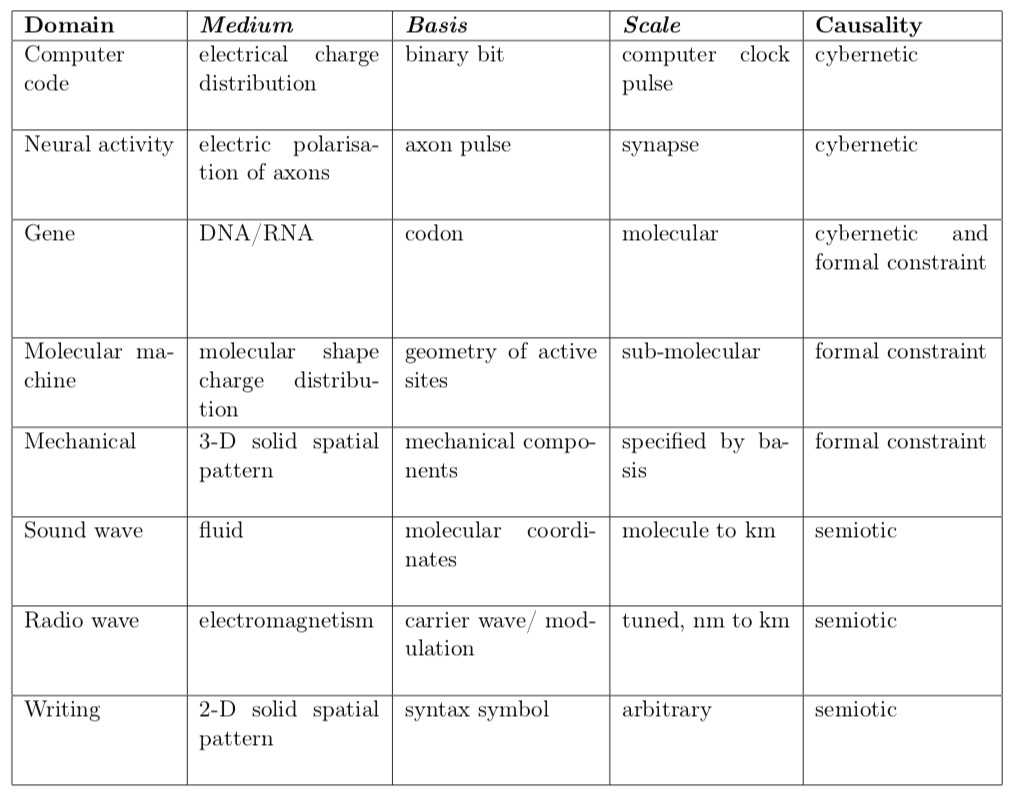

As well as closure to efficient causation, life is uniquely chacterised by codes (genetic being the best known). Realising there are many codes of life gave rise to the subject of 'code biology' led by Marcello Barbieri. Intuitively, ideas of physical information and causal analysis could help us understand why life must use codes and how they work. In [12], I reinterpreted code as a mathematical mapping, resolving the embodiment of physical information (pattern in the assembly of particles) into three fundamental factors: the medium, basis and scale of pattern embodiment - taken together as the domain of embodiment.

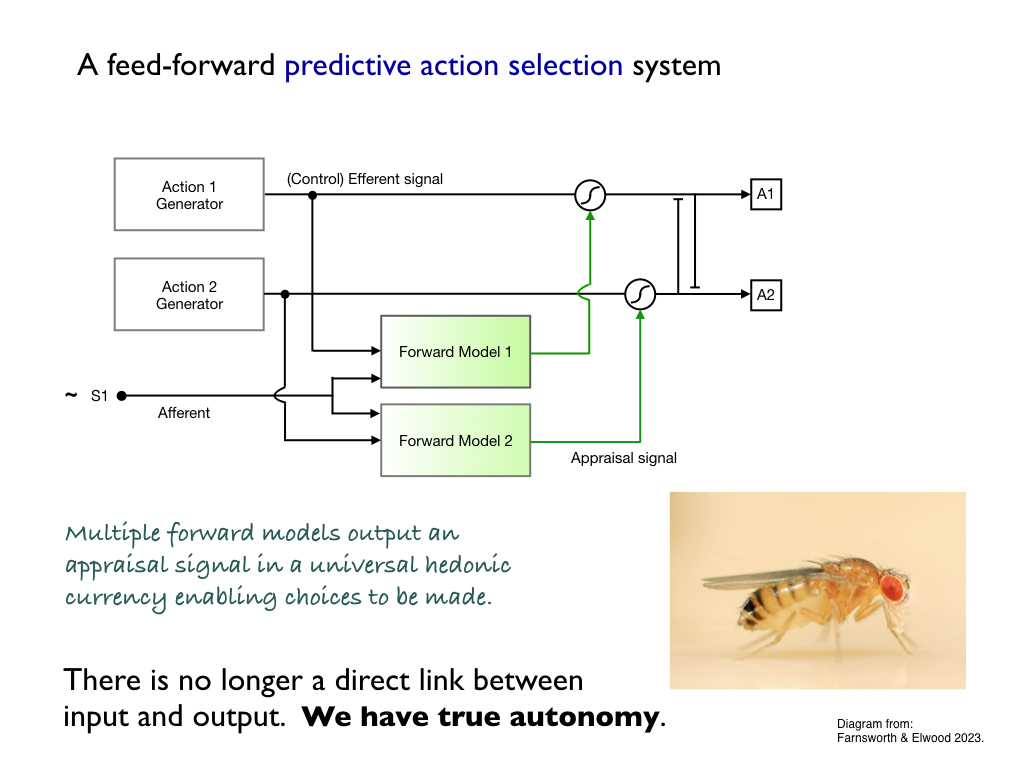

We can build a hierarchy of self-control systems, starting with the

very simplest homeostatic loops. Adding specialist signalling cells

(neurons), enables first, very basic logic control systems, but then

more elaborate decision making logic. This is soon overwhelmed by data

processing demand, so that a generalisable decision making signal is

needed: a goodness vs badness signal that enables a 'quick and dirty',

'rough and ready', appraisal of possible options in an action

selection system. When this system provides anticipatory appraisal it

enables an organism to choose to do what it predicts to be most

beneficial (and the simplest way to implement it is with forward

modelling algorithms) which is easy to put together in neural network

architecture (as depicted below). This sort of thing is typical of

insect decision making systems - many of which have been identified in

their tiny brains. Because the appraisal signal is not directly

determined by any of the perceptive inputs, this constitutes a truly

autonomous decision making system. In [4], animal behaviour expert Bob

Elwood and I showed that this freedom of choice was the biological

justification for pain - why it has to be nasty and strongly

motivational.

For those that are interested, here is a short description of other research I have been involved in.

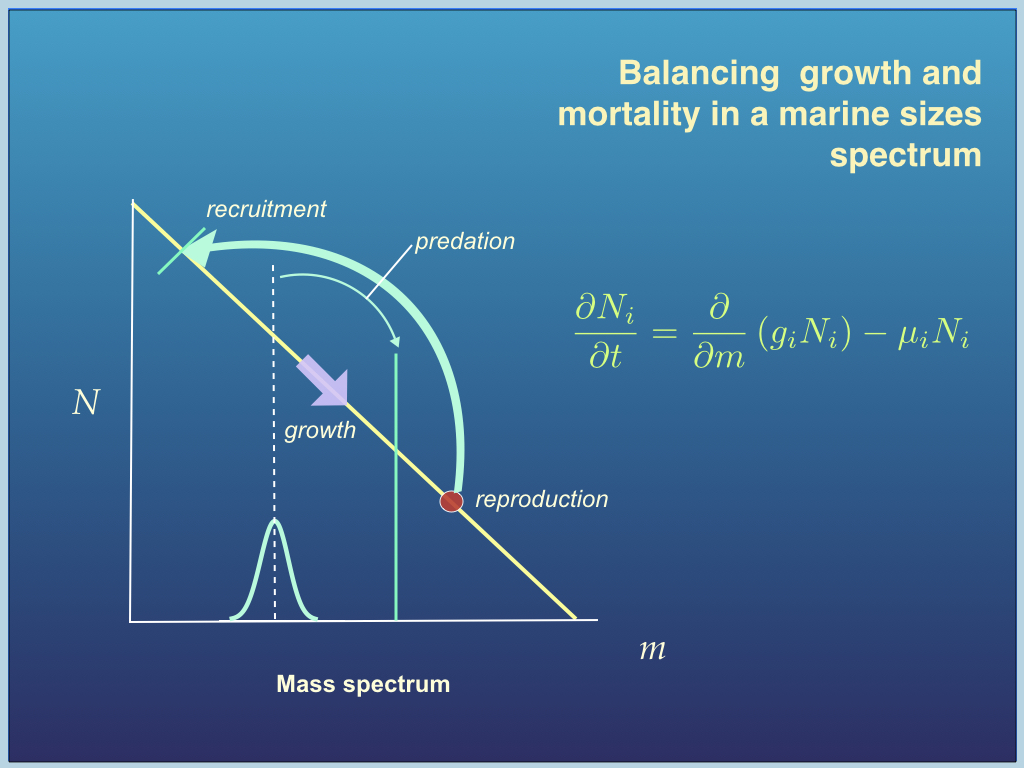

Sustainable Fisheries Management

Fisheries science is an application of ecological theory to practical problems of current real-life importance. It is vital work if we are to save the world's fisheries from the global collapse to which many believe they are heading. A major part of this work is pursued through European Union and Irish Government funding in collaboration with the Danish Technical University. The main project was developing "An Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management". In general, my team and I used multispecies population dynamic models, including recruitment, growth and predation, the core of which (for most of them) was the McKendrick-VonFoerster equation (figure bleow). This work is also being used to create new theories of organism distribution, predator-prey dynamics, life history, and evolution.

Applications to Global Food

Security

Building an 'appropriate technology' management system for artisan

fisheries of the Egyptian Red Sea is the work of an Egyptian PhD student

that I most recently was supervising. It is interesting that this

contributes towards something that the ancient Egyptians of tomb

paintings, papyrus scrolls and pyramids would be quite at home with.

Being pioneers of administration and quantification, I am sure those

ancient Egyptians would approve of the `data limited stock assessment'

methods being deployed and the participatory management processes (they

were certainly not the autocratic tyrants we used to be misled into

thinking). It seems the fishery is over-exploited and declining, so

proper management is urgently needed for this ancient way of life to

survive.In a major collaboration, funded by Science Foundation Ireland, my team helped to devise an alternative to the stock quota system of the Common Fisheries Policy. This alternative is the Real Time Fisheries system, developed by Dave Reid (Marine Institute, Ireland) and Sarah Kraak (Thünen Intitut, Germany), who very sadly died of COVID-19 in 2021. RTI is a high spatial and temporal resolution quasi-economic incentive method which supplies real-time fine-grid tariff maps to operating vessels, using a lot of technology, data and sophisticated modelling.

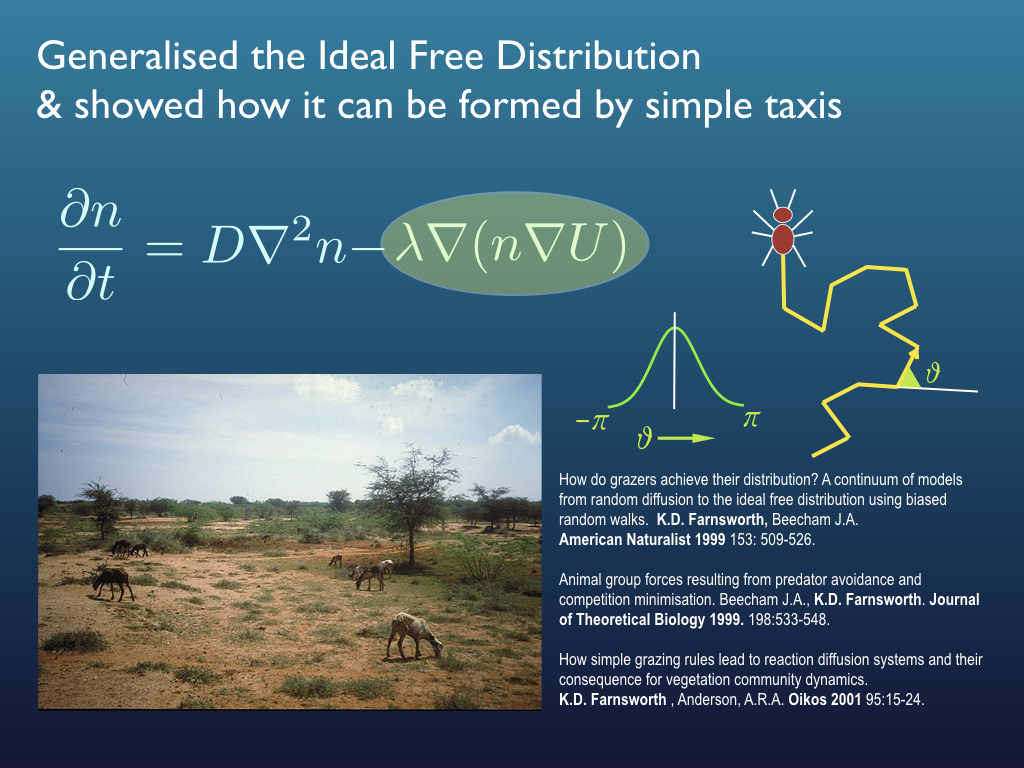

Mathematical ecology

Before fisheries, I developed a theoretical understanding of how large mammalian grazing animals managed to co-exist in the wild and how the effectively distributed themselves to optimise their food resources (leading to some generalisations of the 'ideal free distribution' - a kind of spatial game theory result. On the way, I developed a modification of the foraging functional response for large mammalialn herbivores and this was taken up in several aquatic ecology works through collaboration with Prof. Jaimie Dick and colleagues. Even before that I worked out the optimal growth algorithm for the shape of botanical trees, did a bit of mathematical epidemiology and diagnostic imaging physics involving the UK's first clinical MRI scanner (for the Institute of Cancer Research).