The joy of diversity

The modern high street, or what’s left of it, is now dominated by that handful of big corporate retail brands who collectively make everywhere look the same and a bit, well, plasticky. When I was a wee lad, town was full of specialist traders, each with individual character and often the sort of hand-made chic that is so fashionable in ‘quaint’ and up-market little holiday resorts for the over 50s. The modern is more economically efficient and competitive, the old is more appealing and interesting. That big brand efficiency has largely come about through economies of scale and specifically the eradication of diversity, the same diversity that made the little shops of yesteryear so attractive. Economic orthodoxy says we have traded that appeal for the lower prices we get in the multi-national chains (increasingly trading online from giant anonymous warehouses). We could pay higher prices in little shops, but choose not to, they say. For the record, I often get a better bargain from a small trader than the corporate retailer (and we can wonder who really benefits from their efficiency saving).

We are all economists now

The same has happened in agricultural and forestry land use. Natural, lovely diversity has been traded away for efficiency and management control, economies of scale and ‘comparative advantage’. The economic motive to increase production and efficiency is compelling, but is there an economic counter-argument that defends diversity? In particular, is there anything other than an emotive appeal, a lament for lost species, that can counterbalance the quantitative logic of economic efficiency? Since all public decisions are now economic decisions, anything other than an economic argument will be as effective as pleading your case in ancient Egyptian.

“Call a thing immoral or ugly, soul-destroying or a degradation to man, a peril to the peace of the world or to the well-being of future generations: as long as you have not shown it to be "uneconomic" you have not really questioned its right to exist, grow, and prosper.” ― E.F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful.

For the orthodox economist, the answer is that if people value diversity, they will pay for it. Their conclusion is either that we just don’t value biodiversity as much as efficiency, or that ‘the market’ doesn’t enable us to express our desire to keep it. The market, is of course the price mechanism, by which the value of everything is not only represented, but is defined - even in principle, by its price. No price = no value. Our failure to find a price for biodiversity is, they say, a market failure and the only solution, they say, is to establish a ‘non-market price’: essentially summarising a public opinion survey.

Biodiversity has posed a very difficult problem to those economists who seek a non-market price for it. The problem is that almost nobody knows what biodiversity really is, and people are very easily coaxed into widely different - and wrong - notions of what is in fact a scientific measure of total difference. Followers of www.whatlifeis.info will recognise biodiversity as a measure of information, since an elemental difference is a binary bit: the elemental unit of information. Put in homely terms, the more biodiversity, the more natural knowledge is contained, nurtured and communicated. It sounds nice, but quantifying it leads to a dry and rather opaque accountancy, not something we can easily warm to.

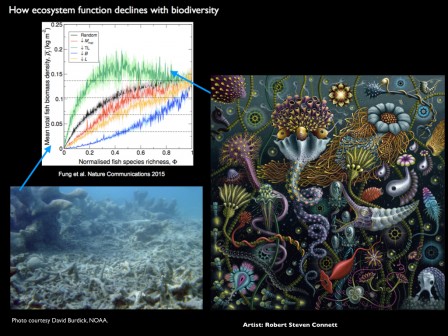

Indeed, when I looked up the value of information, all I found was talk of the utility of knowing more about a problem (especially a financial risk) under uncertainty. By and large, environmental economists have fallen back on asking people how much they value particular species (pandas and all that), or natural environments like woodlands and estuaries. Clearly these are not biodiversity. As scientists, we could seek a relationship between biodiversity and the things people are more likely to value because they generate material benefits for society. Ecosystem services are directly dependent upon ecosystem functions and many ecologists have now discovered correlations between biodiversity and those. But that stuff mostly remains on the academic shelves.

Value is real (what a shock!)

Adam Smith and David Ricado summed the production costs of goods to arrive at a ‘natural value’, Karl Marx emphasised the labour input to this, but efforts like that were abandoned with the advent of Sraffa’s input-output cost matrices and the relativist concept of prices -introduced first because these matrices did not have enough data to solve them. Now we understand production in a more general way, one that transcends human technology and manufacturing. The fundamental and universal factors of production are matter, energy and information, in space and time. That’s because anything that exists in the material world does so because it is a particular arrangement of matter (and energy) in space and time. Every particular arrangement is the embodiment of information and is also the formal cause of everything that can happen (including the fabrication and assembly of all things, from pins to human beings). This new understanding is founded on the theory of the physical basis of causation (see “Biology is no threat to physics” ).

Accounting for biodiversity in terms of information is nothing short of including the largest part of the most precious of the three fundamental factors of all production, and even of causation itself. Because of recent advances in metagenomics and libraries of functional enzymes and the like, we are now in a position to quantify all that information. Doing so will not just provide a comprehensive and sobering account of what we are loosing, it will provide a fundamental basis for calculating the real value of those losses too. The value of information is the same as the loss of the things it is responsible for creating. Taken as a whole, that’s everything.

But as long as economists, and even biologists, continue to think biodiversity is just a count of species, we cannot even begin to formulate an answer. As long as people think the value of biodiversity is how much they are willing to spend on preserving forests and badgers, etc., we will never properly account for the unfolding of the most marvellous development of the universe: life itself.

So come on, state science funders, industry and research charities, set us a sustainable development goal to quantify the accumulated information of life on earth. True biodiversity, with real value.

Credits

photo of degraded reef from https://reefs.com/coral-reef-responses-to-climate-change-and-ocean-acidification-one-size-doesnt-fit-all/