We have to pay for labour because it can be withheld (excluding slavery of course).

We have to pay for capital items (machines etc.) because they are privately owned and therefore can be withheld.

We have to pay for land and commodities as long as they are not ‘public goods’ such as the air we breathe.

But what about information? Although there are exceptions and also legal rights of ownership of certain kinds of information (copyright and patent laws), most information is effectively a public good. Even if it is covered by legal ownership rights, it is easy prey for acquisitive AI agents, lazy plagiarists and copycats. Currently the ‘information age’ is the information ‘Wild West’, where kleptoparasitism is the rule and fakery (e.g. knock-off designer fashion) is the method.

Of course, this matters a lot to the overtly information producers who’s products are at best undervalued and at worst stolen, and redistributed with impunity. Musicians, journalists and free thinkers are all being ripped off so comprehensively now, that it seems very few will remain economically viable. We will all feel the consequence when impartial and independent journalism goes extinct, music regresses into a smorgasbord of recycled chord progressions, beats and emotional word salad and our cultural lives feel like a room of mirrors. Sure, there will be part-time hobbyists (just as I noted the rise of the post-retirement hobby scientist (here)), some very good performing artists among them and people may say “you should be professional” or “on telly”, but we will all know that is not possible, because “there’s no money in it any more”.

That’s a big problem for a national economy relying as heavily on ‘creative industries’ as the UK does. It’s an even bigger problem when we realise that everything we create -- drugs, washing machines, computer chips and oven chips -- is essentially an information product because embodied information is the reason anything is what it is. A chair is an assembly of atoms, each held in a particular place by physical forces whose action is constrained by the information that is the array of coordinates of all those atoms (see explanation here). Production is all about information and all work is information work.

A search for ‘information economics’ or similar, even with google scholar, yields disappointingly meagre pickings - extraordinary when you think how important both concepts are in determining the course of modern life. What I found was a lot of business talk on investment in information technology, web-based sales and marketing and trading in personal data. Pretty dispiriting, but we can do so much better.

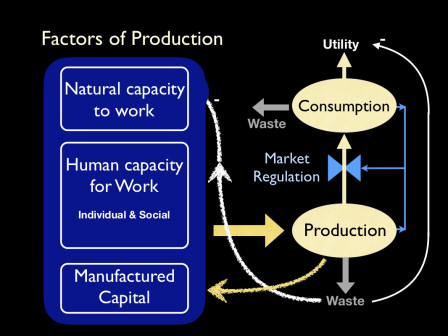

To produce anything at all, factors of production have to combine with functional effect: materials or pieces of information have to be processed and combined, whether it is a chair, a new skin cell or a video game that is being produced. The factors of production are the prerequisites for any capacity to do work, whether that is natural biological growth and development; or human effort - both physical and mental; or the ‘fruit of our labour’ in the form of physical and information processing machines -- collectively known as manufactured capital.

All this needs to be organised as well: generating and maintaining organisation is work too, since it constitutes the assembly of information, opposing the universal trend towards entropy. Thus the capacity to do work, whether by nature to grow a tree, or human effort to knit a scarf, is the capacity of information to constrain energy flow to generate the physical cause of the product.

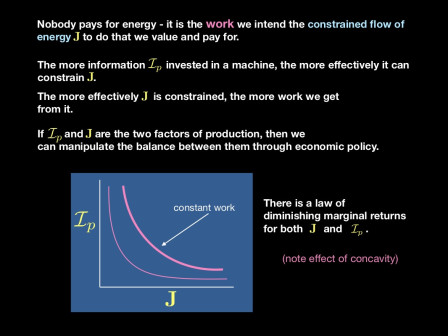

Once information and energy flow are acknowledged as the true, physical, and real factors of production, we can see how they might be traded-off against one another to make a more energy efficient world. In the figure below, points on the energy flow rate (J) / Physical Information (Ip) surface that produce the same work rate form concave curves (the pink lines). Producers can choose the mix of energy and information that is most economically efficient for them (a point on a work rate curve). Society can influence economic efficiency using policies that favour investment in information over (ecologically wasteful) energy use. But the usual and often the best method, which is market-based is not available unless and until we have a market in information. As long as we let society treat information as a public good or allow kleptoparasites to undermine its protection, we cannot have anything resembling a market.

So, I want to say, ‘wake up! economists, realise the importance of information to every kind of production and revise your models to incorporate it, with energy flow, as a fundamental factor of production’. I doubt that will happen, of course, but I will be conveying this message, in more technical detail to the United States Society of Ecological Economics (USSEE) early next year - I hope they will like it.

Acknowledgements.

(The figures shown are from the slides of my talk for the USSEE). Acknowledgement of sources for images are in the figures, but tiny, so: the lady composing at the piano comes from the Society of Independent Muscians; the scientists are from schouxinpan.com and the farmer is from mossgielfarm.co.uk/. The builder is from an unknown source. The diagram showing a model of production is my work, inspired by the '4-factors' model produced by Paul Ekins -- "A four-capital model of wealth creation." Real-life economics: Understanding wealth creation. Routledge: London (1992): 147-155.

Addendum - The primary sector trap

I have been inspired to write more, mainly to illustrate the practicality of what otherwise seems a rather academic point. This addendum section explains the problem posed by raw material producers, its very real effect in the Scottish economy and the only practical solution I can think of.

Economic growth comes from expansion of production and increases in the value of products, which in equilibrium are matched by an increased aggregate value of goods and services consumed. Primary production -- the production and extraction of natural (not manufactured) products -- has very little scope for increasing the value of its output. Beyond quantity, the only possibility is to increase the quality of natural products. Considerable effort has been spent on doing that: in agriculture (disease free, standardised, ‘organic’ early, fresh, tastier, healthier, food), in forestry and fisheries (sustainable, selected quality, etc.) and in mineral products (higher purity). But compared to the opportunities available to secondary and tertiary sectors, the per-unit value gains in the primary sector are meagre. So as the economy as a whole grows and this in turn stimulates rises in real wages, the primary sector must reduce its labour costs by substituting labour with physical capital, but still falls behind the growth potential of secondary and tertiary sectors (to which it pays higher rates for its increased use of manufactured capital).

The result of this primary sector trap is that primary products tend to become cheep in comparison with manufactured good and services, since the only way the primary sector can keep up is to use economies of scale to produce huge quantities at relatively little production cost, so that the equilibrium price for primary products is kept low. Given this, the cost of replacing a manufactured product is usually less than the cost of renewing it (by repair, refurbishment or recycling). This would likely still be true even if the full cost of disposal of waste is internalised to the costs of production of manufactured goods. The, much vaunted, ‘circular economy’ is fouled by this primary production trap.

Can you see what lies at the heart of the trap? Primary production is all about 'stuff'. When we process it (refinement, mixing, fabricating and assembling), we add physical information to it. Adding value is adding information.

Hypothetically, there are several ways out of this trap, but all of them introduce substantial market ‘distortions’ and inefficiencies. First, and perhaps least economically distorting, is the vertical integration of production, whereby a single economic agent is producer of, at least, the chain from primary to secondary products, e.g. the farmer producing cheese and the ore miner producing steel components. The problem with this is that it removes a degree of market-led regulation matching the production of raw materials to demand in competition. Over time, vertically integrated agents may become inefficient because competition over primary products is hidden within the internal production process. Still, competition among these vertically integrated agents should stimulate progress in their technical and economic efficiency, just perhaps not as effectively as if they were vertically divided as specialists.

The second way out is to apply market distorting support for the primary sector, as in agricultural subsidies. Since agricultural employment is an important part of rural life in most countries, this can be justified on social (and increasingly, on ecological) grounds. Conversely, it would seem perverse to distort the market in favour of e.g. fossil fuel or metal producers, who a) are doing just fine and b) make stuff that, being ecologically concerned, we wish to reduce.

The reason for both (a) and (b) is that these primary industries have already found such economies of scale and such substitution of capital for labour, that they are efficient enough to keep up with the secondary sector (for now at least) and also of relatively little social importance as employers (barring local effects such as coal mining communities and the local economy of cities heavily reliant on a single industry (offshore oil in Aberdeen and oil refining in Borrowstouness (Grangemouth) to give two contemporary Scottish examples). Indeed it could be said that in Scotland, government policy has penalised these primary sector components by adding additional taxes (the UK Energy Profits Levy - windfall tax) and, ironically, energy cost burdens (the stated main reason for steel, cement and refined oil producers closing). The position would be very different if, hypothetically, fossil fuel production was pursued by a large number of small enterprises, each employing a relatively large workforce that in total composed a socially and politically important part of the population. In other words, it is the very efficiency of these primary producers that makes them targets for the Chancellor, social critics and ecological concerns. Therefore, equally hypothetically, a third way of distorting the market to both reduce fossil fuel production (raising energy prices, thereby lowing consumption) and maintain primary producers, would be to fragment the huge companies currently operating and support them through a government managed economy for energy. That would have to include a very substantial subsidy to ensure energy consumers can transition to lower demand without going out of business (firms) or freezing in their own homes (domestic consumers). None of that is remotely practical.

One radical ‘green’ proposal is that “we already have enough stuff”. We could make do with all the manufactured goods presently in existence and just renew them as required by repair and recycling, thereby reducing the need for de-novo secondary production (substituting recycling as compensation) and dramatically reducing primary production, other than for biological consumables (especially food, of course). This would be a final defeat for the non-food primary producers, an admission that after all the effort to keep up, their time had come and, as we have seen throughout the UK coal industry, it was time to hang up the hard hats and call it a day. Rather than having that workforce languish on benefits, we would of course want to direct them towards the growing recycling, refurbishing industries and the still rapidly growing service sector, especially where demand for information services is now outstripping supply. That is stated government policy already, but far easier said than done. Presently, I can see very little evidence of it in practice. It is a very urgent and appropriate task for governments at all levels. Investing in human minds (information) to enable them to take part in producing information services may turn out to be the best way of easing the fossil fuel burden on the climate.

Contemplating what constitutes objective truth and what happens when we reject it -- nothing good!

Contemplating what constitutes objective truth and what happens when we reject it -- nothing good!